By Carina Peritore, PhD, Product Manager, Neuroscience Discovery at Charles River Laboratories

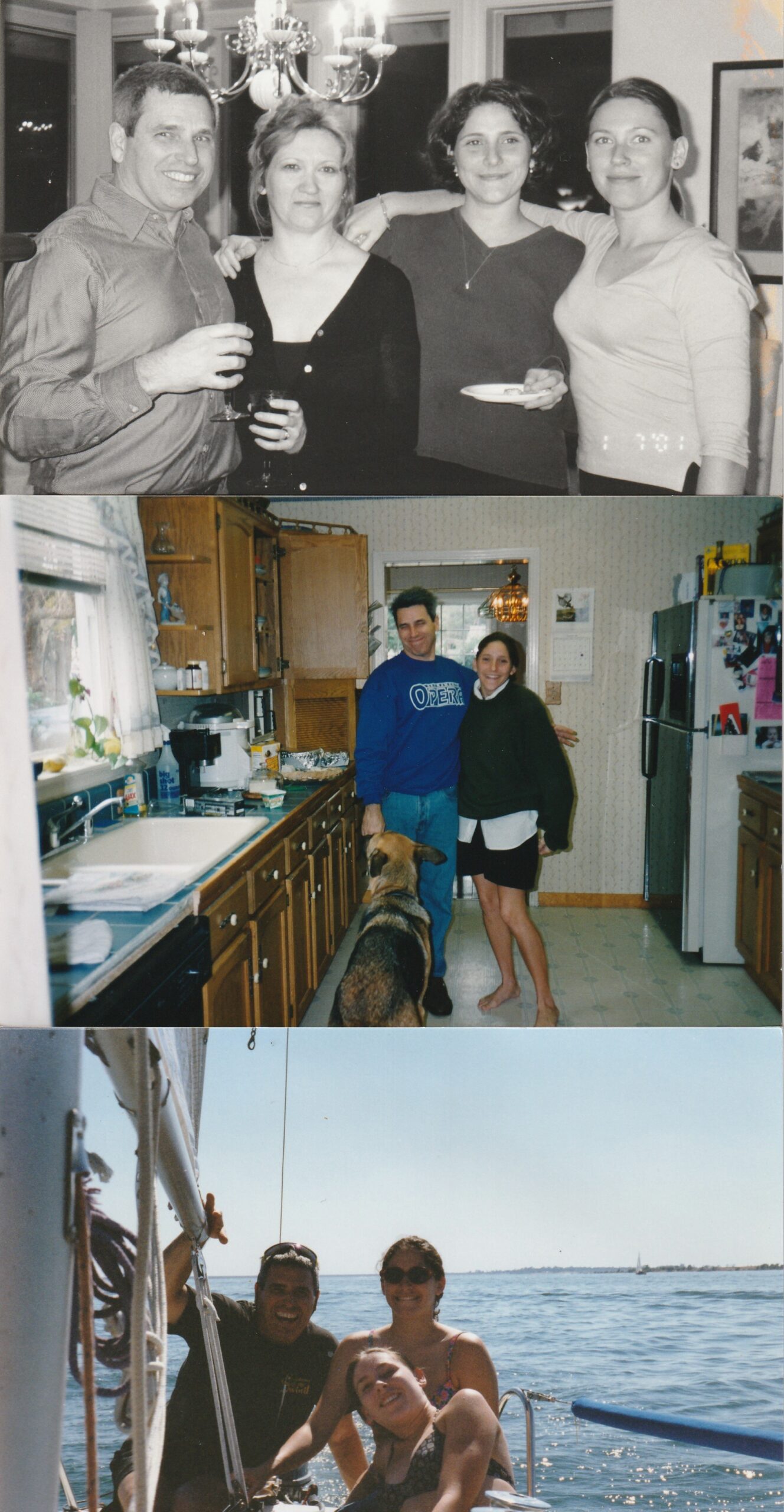

I come from the typical melting pot of an American family. I was born unto a second-generation German Irish mother and Mexican American biological father and Sicilian American adoptive father. My last name used to be Spanish, Garza, until Michael Peritore officially adopted me in 1989. I was twelve years old. I was eight when Michael and my mother Sherrie were married. But he was my father from the time I can remember existing on this planet. With him, he brought my sister, whose mother came from Polish decent. In our second marriage family, people often thought I was Michael’s biological daughter with my darker complexion and darker hair. And my sister to Sherrie with her fairer complexion, lighter hair and blue eyes. Yet it was the other way around! I usually don’t bother with the details of it all and just say, yeah, I am Sicilian.

But this story isn’t about my heritage or roots. It’s about my father, Michael Anthony Peritore. Michael was not an ordinary man. He was 51 years old when he began having some odd and perplexing symptoms. He felt light-headed often, every time he stood up. He started drinking more water thinking he was just dehydrated. He was drinking so much water that he noticed his skin was getting softer. But the lightheadedness was only getting worse. He complained that at times he heard a “shhhh-ing,” sound in his ears. We had no idea what to make of that. Within one year, he was using a walker because his balance was so off that he walked as if he were drunk. His speech began to slur. His emotions went awry. He would cry at a sentimental commercial on television and laugh uncontrollably at others.

But this story isn’t about my heritage or roots. It’s about my father, Michael Anthony Peritore. Michael was not an ordinary man. He was 51 years old when he began having some odd and perplexing symptoms. He felt light-headed often, every time he stood up. He started drinking more water thinking he was just dehydrated. He was drinking so much water that he noticed his skin was getting softer. But the lightheadedness was only getting worse. He complained that at times he heard a “shhhh-ing,” sound in his ears. We had no idea what to make of that. Within one year, he was using a walker because his balance was so off that he walked as if he were drunk. His speech began to slur. His emotions went awry. He would cry at a sentimental commercial on television and laugh uncontrollably at others.

His neurologist gave him a diagnosis of cerebellar ataxia due to his low blood pressure upon standing. What we learned with our own research is that this was a symptom of a larger disease. But what was that larger disease? It read like Shy-Drager Syndrome or OPCA (Olivopontocerebellar Atrophy). None of which was good.

Another year later, my father was in a wheelchair. He was beginning to lose some of his autonomic nervous system functions and developed a tremor in his left arm. He was 53 years old. He was being treated with levodopa which alleviates Parkinson’s-like symptoms including the tremor, yet he was not responding at all. I madly searched for doctors that specialized in movement disorders and interviewed our family members for any insight into this being hereditary.

By the time my father was 54, we got a diagnosis. An MD PhD at UC Davis Medical Center who specialized in movement disorders reported that his brain MRI indicated a shrinking cerebellum. His diagnosis after years of unknowns was a disease called Multiple Systems Atrophy, otherwise known as MSA. There are two forms of MSA. One is called MSA-C and the other MSA-P which depends on the most prominent symptoms at the time the individual is evaluated. Because his primary symptoms featured ataxia, it reflected MSA-C for cerebellar.

My father was relieved to have an answer to all the symptoms he was experiencing. Yet at the same time, we were horrified at what was to come. MSA progresses more rapidly than Parkinson’s Disease and the prognosis is six to eight years. My father, once an accomplished sole practitioner lawyer, control-freak, sailor, and opera singer was bed-ridden by the age of 57 with a feeding tube and unable to speak. He blinked once for yes and twice for no. His mind was intact, yet his body out of control.

My father passed away at 58.

During my graduate studies, I started a joint project with both my PI at Boston University in an organic chemistry lab and a professor at the medical campus studying neurodegeneration. This was the beginning of a life-long journey for me. Not only was I curious about pursuing a research career in neurodegeneration but also helping to raise awareness about MSA.

It took so long for my father to get a diagnosis, and I realize now that it doesn’t have to be that way. Upon discovering the MSA Coalition through a support group in the bay area of California, it became evident to me how similar my father’s story was by connecting with other patients and caregivers in the community. It was also most promising to discover the likes of Professor Gregor Wenning and Dr. Vikram Khurana researching the mechanism of this terrifying disease and pushing forward the discovery of promising therapeutics.

During the first Patient & Family Conference I attended, the opening speaker said the words, “MSA is nature’s cruelest experiment…” and that stuck with me from that day forward. I thought how accurately he portrayed the progression of this disease and the genetic material that created it for the human population. I have never wavered from that thought.

My only regret is that I didn’t discover these resources until shortly before my father passed away. I wish I could have given him the opportunity to connect with other patients suffering from MSA. And for my mother, other caregivers of MSA. And for me and my sister, peace of mind that we were not alone. That is what the MSA Coalition achieves. Between patients, caregivers, researchers, doctors, fundraisers, and general awareness, the MSA Coalition connects us all. One by one, team by team, and community by community.

No matter how much time has passed between my father’s first encounter with the symptoms of MSA and ultimately toward his death and beyond, I always gravitate toward the MSA Coalition. What can I do now to help? I’ve utilized my career to provide insight and charity. But what else can I do? How can I help so that not another patient has to die that way?

Carina shares her personal experience with MSA in this session recording and this podcast.

Carina Peritore, PhD is a product manager at Charles River’s Neuroscience Discovery units based in Finland, South San Francisco, The Netherlands and the UK. She has a PhD from Boston University and completed her postdoctoral studies at both Tufts University School of Medicine in the Neuroscience Department in Boston, MA and Pfizer in Groton, CT.